E-cigarette Use May Alter Healthy Nasal Mucosa

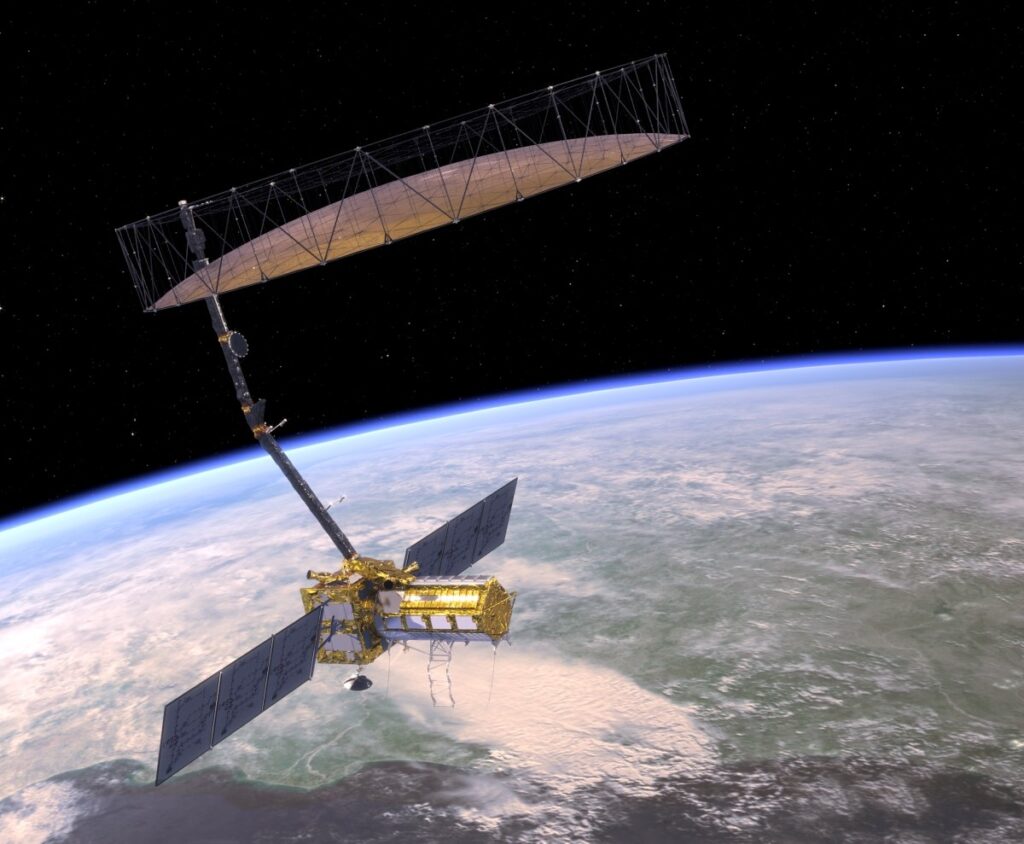

NASA Space Technology

E-cigarette users and smokers had significantly higher amounts of Staphylococcus aureusin their respiratory microbiome than nonsmokers, and microbial diversity differed by sex, according to a new analysis. Researchers in a new study also found that Lactobacillus inersusually seen as a protective species, was more prevalent in smokers than in nonsmokers, whereas less prevalent in e-cigarette users than in nonsmokers.

The respiratory microbiome is thought to help protect the lower respiratory tract from pathogens, but the specific effects of e-cigarettes on the respiratory or nasal microbiome have not been well studied, wrote Elise Hickman, PhD, of the Center for Environmental Medicine, Asthma and Lung Biology at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

“Identifying how e-cigarette use modifies the nasal microbiome is another step in understanding how vaping affects lung health,” said lead investigator Ilona Jaspers, PhD, in an interview.

In a study published in Nicotine & Tobacco Researchthe investigators used 16S rRNA gene sequencing to examine the respiratory microbiomes of 57 healthy adults aged 18-50 years: 20 nonsmokers, 28 e-cigarette users, and 19 smokers. The researchers collected serum cotinine measurements as an indicator of nicotine exposure, and participants completed questionnaires as to their smoking habits.

Smokers reported an average of 12.68 cigarettes per day. The 13 e-cigarette users who reported puffs per day averaged 53.90 puffs per day, and the 16 who reported mL of liquid per day and e-liquid nicotine concentration averaged 3.60 mL of e-liquid and 19.43 mg/mL of nicotine in e-liquids.

Overall, the researchers found an increase in S aureus in smokers and e-cigarette users compared with nonsmokers. By contrast, L iners was more abundant in smokers than in nonsmokers but less abundant in e-cigarette users than in nonsmokers.

Notably, among e-cigarette users, the microbial beta diversity was significantly different between male and female participants, although this was not the case in cigarette smokers.

For example, Propionibacterium acneswas decreased in smokers and e-cigarette users compared with nonsmokers. However, men demonstrated an increase in Haemophilus parainfluenzae and P acnes and a decrease in S aureuscompared with women.

The researchers also stratified smokers and e-cigarette users into groups based on cotinine (a nicotine metabolite) to examine the impact of nicotine on changes in the nasal microbiota. Among smokers, microbial diversity was significantly decreased in those with cotinine levels> 151 ng/mL vs those with cotinine levels 151 ng/mL. However, the opposite was true for the e-cigarette users (P <.05 for both).

“We were surprised by the clear sex differences in the nasal microbiome,” Jaspers told Medscape Medical News. “While we have previously shown sex-dependent differences in exposure-related changes in the nasal mucosa, finding sex differences in the nasal microbiome was new and surprising to us. We were not surprised by the changes in microbiome seen in cigarette smokers; these changes have been observed before,” she noted.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the diversity of factors that could affect the participants’ e-cigarette exposures, including e-liquid flavor, type of device, nicotine content, and frequency of use, as well as the small sample size and variations in completeness of the questionnaires, the researchers wrote. When stratified by gender, S aureus was more abundant in women vs men, they said, but the cross-sectional study design prevented measurement of whether this increase correlated with increased disease risk.

However, the results support previous research showing an effect of inhaled toxicants on the respiratory microbiome and provide robust evidence of sex differences, the researchers said.

Changes in the microbiome, regardless of location, have been linked to a range of diseases, Jaspers told Medscape Medical News. “The gut microbiome is now explored as a therapeutic target, with probiotics being an example. In the respiratory tract, some investigators have suggested to use similar approaches for the nasal microbiome,” she explained. “Understanding whether and how e-cigarette affect the nasal microbiome may provide clues to causes of respiratory diseases and potential targets for interventions,” she added.

The current study was unable to control for none-cigarette vaping devices such as increasingly popular tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) vaping devices, said Jaspers. Many of the e-cigarette users in the study were dual users and also vaped THC, and how and whether THC affects the nasal microbiome is an important area for further research, given the popularity of these devices, she said.

NASA Space Technology Early Research, Interesting Results

Given the persistence of e-cigarette use in adolescents and adults, the current study aimed to address the knowledge gap in how e-cigarette use affects the nasal microbiome, which plays a crucial role in respiratory health, said Dharani K. Narendra, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, in an interview.

“The findings showing sex-dependent differences in nasal microbiome dysbiosis, particularly in e-cigarette users, were notable,” Narendra said. “While previous studies had demonstrated differences in immune responses based on sex, the extent to which these differences manifest in microbial composition was unexpected. Additionally, the discovery that specific bacterial species behaved differently between smokers and e-cigarette users highlighted the distinct impacts of these exposures,” she noted.

“The key clinical takeaway from the study is that both e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking are associated with distinct nasal microbiome dysbiosis, which may predispose users to respiratory infections and immune dysfunction,” Narendra told Medscape Medical News. “Additionally, these effects are sex-dependent, particularly in e-cigarette users, highlighting the importance of considering sex as a biological factor when assessing the health risks of e-cigarette use,” she said.

“Clinicians should be aware that e-cigarette use is not without health risks and may influence respiratory immunity in ways that differ from traditional cigarette smoking,” Narendra emphasized. The current study can inform assessment of patients based on their smoking or vaping habits and implementation of preventive measures to protect against dysbiosis-related respiratory conditions, she added.

“The study’s limitations include the relatively small sample size, variability in e-cigarette use patterns, such as nicotine levels and device types, and the fact that some e-cigarette users were former smokers, which might have influenced the results,” Narendra told Medscape Medical News. “Future research should expand cohort sizes, account for more detailed e-cigarette usage parameters, and utilize advanced sequencing methods to obtain higher-resolution insights into microbial changes,” she said. Longitudinal studies are needed as well to investigate how microbiome dysbiosis correlates with disease development and progression, Narendra noted.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Narendra had no financial conflicts to disclose but serves on the editorial board ofCHEST Physician.

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings