At the presidential debate, fossil fuels and energy politics took center stage

Politics tamfitronics

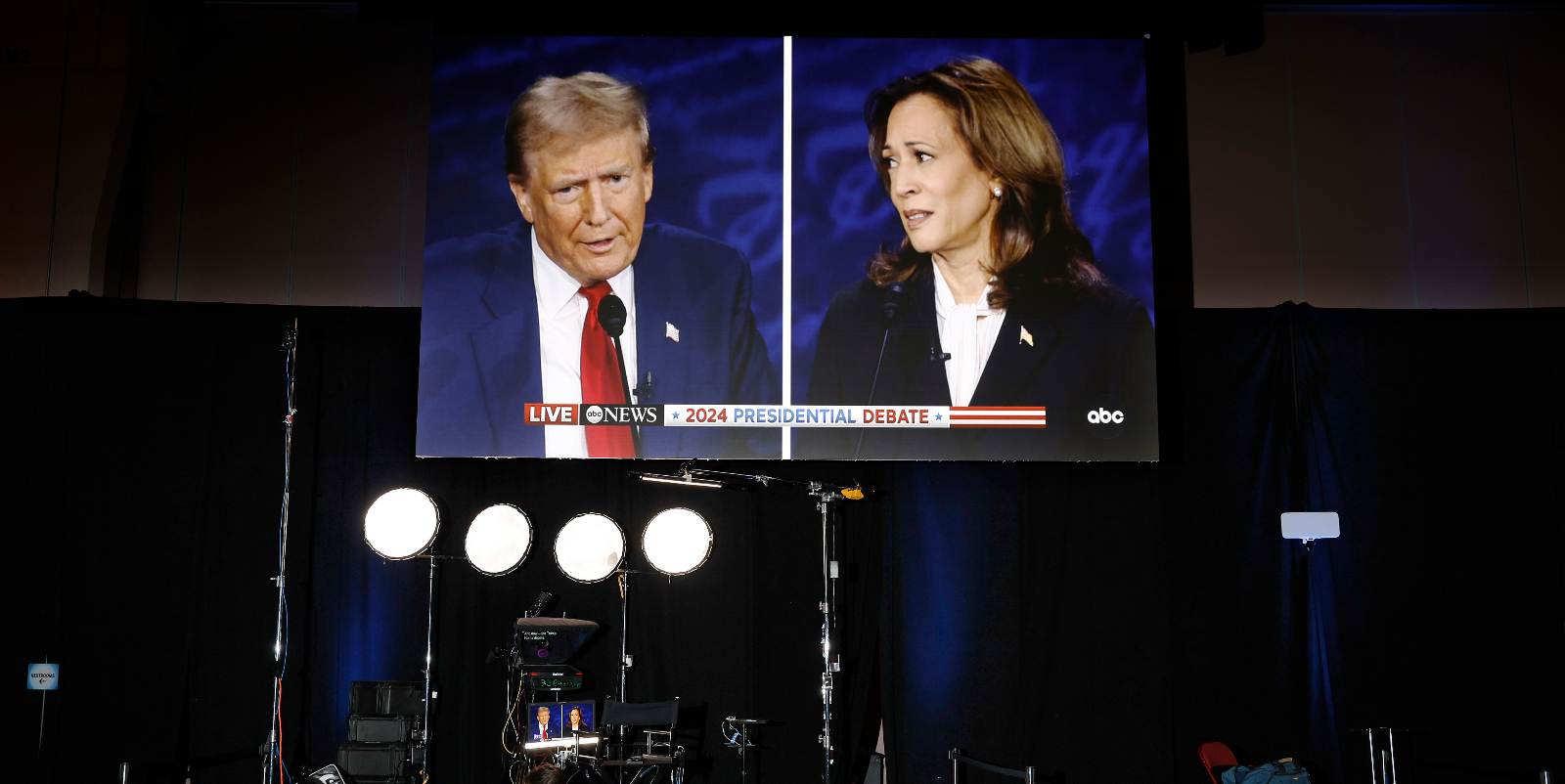

A month ago, it seemed unlikely that Vice President Kamala Harris would ever reach a goal she set out to achieve as a presidential hopeful in 2019. But at 9 p.m. on Tuesday night at the National Constitutional Center in Philadelphia — five-odd years after she dropped out of her first presidential race — Harris finally faced off against Donald Trump in what will likely be the only debate between the two candidates before Election Day.

Harris and Trump are diametrically opposed to each other on issues ranging from national security to the economy to foreign policy, but perhaps nowhere are the candidates more at odds than on the matter of climate change: One thinks rising temperatures pose an existential threat, the other thinks climate science is nonsense.

That gulf in views was put on full display in the last minutes of the hour-and-a-half-long debate, when ABC News Live Prime host and debate co-moderator Linsey Davis asked the pair what they would do to fight climate change. Harris, who answered the question first, was quick to point out that Trump has implied on many an occasion that climate change is a hoax propagated by China. “What we know is that it is very real,” she said. “You ask anyone who is living in a state who has experienced these extreme weather occurrences who is now being denied home insurance or it’s being jacked up.” In the past couple of years, private insurance companies have begun dropping policies in fire- and -flood-prone states like California and Florida.

While Harris pointed out the existence of these worsening problems, she did not say what she plans to do about them, choosing instead to cite investments in climate change made by the current president. “I am proud that as vice president, over the last four years, we have invested $1 trillion in a clean energy economy, while we have also increased domestic gas production to historic levels.” She got that $1 trillion sum by adding up all of the administration’s major investments over the past four years, some of which are only vaguely connected to climate change.

Trump didn’t answer the question at all, instead making a convoluted point about domestic vehicle manufacturing. He then falsely claimed that President Biden is getting millions of dollars from China and Ukraine. “They’re selling our country down the tubes,” he said.

Trump slashed scores of environmental rules and climate regulations during his four years in office and appointed three conservative Supreme Court justices who have since made it harder for the federal government to clamp down on pollution. He also withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement, a global pact to slow planetary warming, though President Biden later reentered it.

Before Tuesday’s debate, it seemed likely that Harris would cite her record as district attorney for the city of San Francisco, where she formed the nation’s first environmental justice unit aimed at penalizing companies for polluting. Or her tenure as California attorney general, when she investigated oil companies and secured a multibillion-dollar joint settlement from Volkswagen over the company’s attempts to cheat smog emissions standards. But she didn’t bring those receipts to the podium.

Instead, Harris doubled down on her recent efforts to make swing state voters in gas-rich states like Pennsylvania forget about the anti-fracking position she took during her 2019 presidential campaign. At the time, Harris said she was “in favor of banning fracking,” but she recently walked that back. “I will not ban fracking,” Harris said early in the debate. “In fact, I was the tie-breaking vote on the Inflation Reduction Act, which opened new leases on fracking.” The Inflation Reduction Act also happens to be the single largest investment in fighting climate change in American history, something Harris chose not to point out.

Rather, she advocated for an energy strategy that has been proposed by many Republican lawmakers over the years: something resembling an “all of the above” approach in order to boost American energy independence. “My position is that we have got to invest in diverse sources of energy, so we reduce our reliance on foreign oil,” she said.

“Harris spent more time promoting fracking than laying out a bold vision for a clean energy future,” the Sunrise Movement, a youth climate action group, said in a statement. “We want to see a real plan that meets the scale and urgency of this crisis.”

Harris wasn’t the only one eager to talk oil and gas at the debate. Onstage, Trump frequently returned to a familiar set of energy-related talking points. He skewered President Biden, and Harris by association, for high gas prices, which spiked again this year. He claimed that the day after the election, should Harris win, “oil will be dead, fossil fuel will be dead.” Neither Harris nor Biden have ever said that they aim to eliminate the country’s vast reliance on fossil fuels in the near future.

Trump also went after sources of renewable energy, saying that, while he is a “big fan of solar,” Democrats have commandeered “a whole desert to get some energy out of it.” Trump may have been referring to parts of the American West where the Bureau of Land Management has approved 33,500 acres of land, some of it desert, for solar installations since 2021.

As the debate wrapped up, it wasn’t clear whether Harris had succeeded in her goal of convincing Pennsylvania voters that she’s not the anti-fossil fuel crusader Trump has been working to pin her as. But she did leave Philadelphia with at least one coveted endorsement: that of pop icon, and native Pennsylvanian, Taylor Swift.

“I’ve done my research, and I’ve made my choice,” Swift wrote in an Instagram post shortly after the debate ended. “I will be casting my vote for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz in the 2024 presidential election.”

Jake Bittle contributed reporting to this article.

Discover more from Tamfis Nigeria Lmited

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings