Hurricanes are personal for this disaster researcher

Politics tamfitronics

This story is part of State of Emergencya Grist series exploring how climate disasters are impacting voting and politics. It is published with support from the CO2 Foundation.

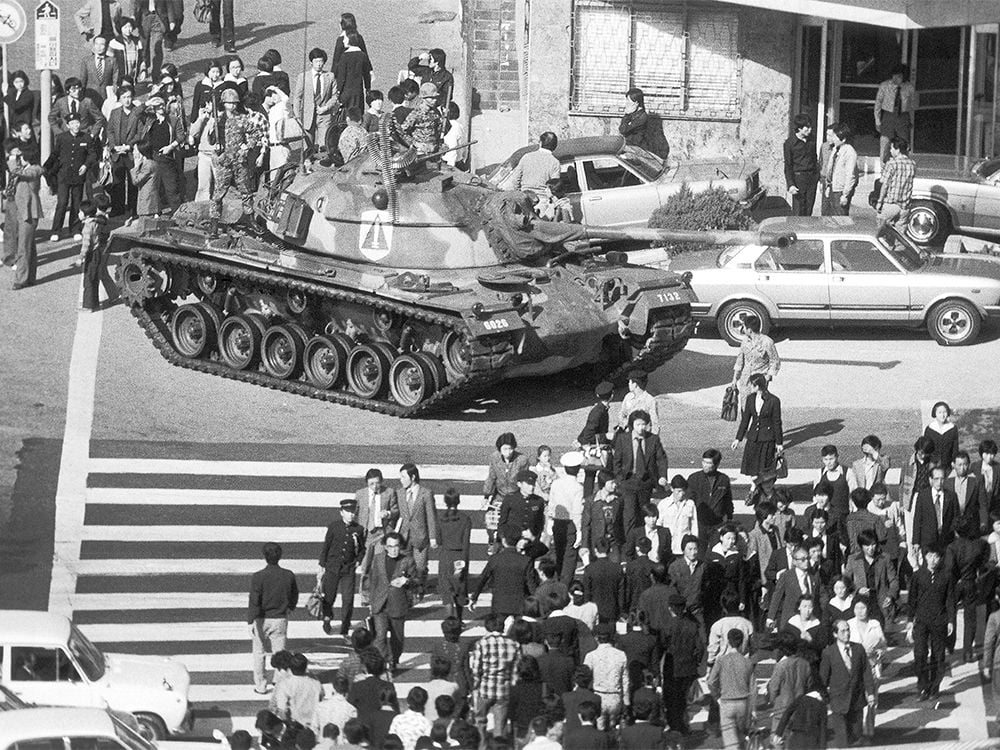

In the spring of 2005, Daniel Aldrich, a researcher, was finishing his doctorate in Japanese energy politics at Harvard University. That summer, he moved to Louisiana with his wife and two young children, renting a house in New Orleans to begin his first-ever job in academia at Tulane University. The campus was abuzz in late August as students moved into their dormitories and teachers prepared for the first day of classes. The last Monday of that month was supposed to be Aldrich’s first day of teaching. He never made it to campus. Twelve feet of water had turned his house, eight blocks from Lake Pontchartrain, into a swamp, destroying everything he owned, including his car, and sending his life in a totally new direction.

Hurricane Katrina made landfall in southeast Louisiana as a Category 4 storm the morning of August 29, 2005, leading to more than 1,500 deaths in three Southern states and causing $300 billion in damages. In New Orleans, poor city planning and lack of flood resilience made a bad situation worse. Some 80 percent of the city was underwater 48 hours after Katrina hit. It would take many months for the people who evacuated to come back. A portion of the population never returned, and the city still bears the scars of Katrina’s impact, and the recovery process — botched by bad politics, racism, and lack of foresight — that followed.

The Aldriches evacuated to Texas first, then moved back to Boston, where they stayed in an apartment rented for them by sympathetic friends and family. They watched on television as thousands of people, trapped in the Louisiana Superdome, begged for water and medical supplies. One close friend was evacuated from his rooftop by helicopter and dropped off at the airport, where there wasn’t enough food to go around.

Aldrich and his family didn’t go back to New Orleans for months, until that January. “That’s when we saw the on-the-ground horrors,” Aldrich said. On the walk from his house uptown to Tulane, little springs of water would shoot up out of the ground every few steps. The weight of the floodwater had crushed the city’s underground infrastructure. Finding a doctor was next to impossible. Grocery stores weren’t stocked. Abandoned boats blocked the streets. They didn’t last more than half a year. Aldrich got a job offer in Massachusetts, and the family went north again. In Boston, Aldrich’s children were tested for lead, a city requirement. Levels of the toxic metal in their blood had tripled while they were in New Orleans, where floodwater and post-hurricane demolition had sent the lead in the paint coating many of the houses in the city swirling into the environment.

Courtesy of Daniel Aldrich

Katrina marked a turning point in Aldrich’s life, and in his professional trajectory. He would spend the next two and a half decades researching the politics of disasters and disaster resilience, writing three books on the subject and becoming one of America’s foremost disaster resilience experts. And he would soon find that epochal disasters like Katrina are radicalizing — often representing an individual’s first interactions with the federal government. That experience, his research has found, can end up dictating political preferences and voter behavior.

Most importantly, Aldrich learned that survivors tend to become more civically engaged post-disaster: They run for office, start community groups, and show up at town meetings. Aldrich, used to sitting outside of the research he was conducting, realized that he had become a data point himself. “Hurricane Katrina destroyed my home, my car, and everything that I owned,” he said. “For me, it certainly changed my perspective.”

Grist spoke with Aldrich, now a professor of political science at Northeastern University, about his post-disaster experience, how climate shocks like hurricanes affect voters, and how Americans’ expectations of how the federal government should respond to a disaster have changed over time. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. What happens, politically, to voters after a disaster? How does their behavior change?

A. There’s a lot of interesting research on this question. I think there are two things we have to think about. One is, what happens in terms of voting itself? Do people turn out to vote more than they would have in a normal year, not a disaster year or month?

Some people argue that civic engagement as a whole increases for survivors of disasters. They’re more likely to vote, more likely to run for office, more likely to contact a congressperson, more likely to get involved in a meeting. There’s really interesting before-and-after studies of survivors themselves.

But then, the second question is: When they do that, whom do they vote for, and what happens then?

Typically, most of us don’t really encounter the government, except in moments like getting our driver’s license or passport renewed. But during a disaster, the vast majority of us begin to, because we’re applying for some kind of aid. Rather than being some abstract entity, now there actually is an agency in the government you’re interacting with. You think, ”Oh my God, I’ve been paying taxes since I was 22 or 23. Here’s my chance to get my money back.”

This is the funny thing about being both a survivor of a disaster and a scholar involved in studying disasters. My FEMA application was rejected in the first six months after Katrina. So that did not go well for me, but for other people who it goes well for, you can get thousands of dollars. So either people are really pissed, like me, because they didn’t get what they wanted. They want to punish the government. Or they’re thrilled. They got something. The government actually came through.

Q. Given that spectrum of sentiment around disaster relief — where some victims get what they want, and others hit brick walls — what are the repercussions for politicians?

A. A lot of data has shown that in flooded areas, people tend to show up to vote in higher numbers for the incumbent party. Why is that? The party in power, if they’re smart, begins pumping a lot of extra stuff in. They pump extra personnel assistance and assistance to businesses, to schools, or just road infrastructure. The levers of power allow the incumbent party to begin showering all kinds of, as we call them, pork barrel politics, or electoral goods, back into those communities.

If you look at the number of disaster declarations in an election year, they’re statistically higher than in non-election years. Even a small disaster — a tanker truck overturns and blocks I-40, there’s a fire in someone’s backyard and six people are made homeless — the party in power can take even this small thing and turn into a bigger one again, to get more aid, get more systems going, specifically, more disaster declarations. It feeds back to this idea that the party in power is using those levers of power during that short period to try to attract voters.

This is very deliberate. And you can say, “I’m really helping everybody,” and that it’s nonpartisan to defend yourself. You can say, “Well, look, I’ve got Democrats, some Republicans in my district. I want to make sure everyone is safe.”

There are also people who have argued — using flooding again, because flooding is very common — that there’s as much likelihood of people punishing the party in power as there is supporting the party. When Katrina flooded my house, I was very angry. We had to fax our FEMA application in, and we were on the road to Houston stopping in, like, Kinkos, trying to fax it in. I cannot tell you how frustrating that process was, and then it got rejected.

Q. Can we talk about FEMA? For many people, belief in or mistrust of FEMA almost comprises its own political affiliation. The agency tends to bear the brunt of people’s anger, right?

A. We envision FEMA as a white knight: FEMA guys in tents handing out food. That’s not what they do. And there’s very few FEMA employees to begin with. Their job is literally to say to a state or local representative, “Nice job, you built a hospital, now we’re writing a check to reimburse you.” That’s what they are, they’re a check-writing organization. But the expectations we had as a nation used to be very different.

More than 100 years ago in Boston, we had the Great Molasses Flood that killed nearly two dozen people. A huge molasses tank broke and all that molasses went through the downtown, picked up people, and they drowned, because you can’t breathe it, you can’t swim out of it. The bottom line is that when that happened, even though you’d think, “OK, this is a great time for the national government,” no one got involved besides local organizations. It was all like churches, synagogues, and mosques, and the local Boston city office got involved, and the expectation that disasters were a local problem continued really until World War II.

And then by the 1950s and ’60s, when we had this whole “nuclear bombs are coming” Cold War thing, we went from Americans expecting the federal government to do nothing to now expecting a lot from the government. And that gap between expectation and reality began to put pressure on FEMA. It’s not really FEMA’s job to rebuild, that’s not what they do.

Q. It seems like a bad situation — that FEMA wasn’t built for what people expect it to do, and also that climate change is making these extreme-weather events happen more often and with more intensity.

A. The number of shocks that we have, the number of disasters that we have, are happening more often, and the shocks that are happening are more impactful. We have this data going back 100 years. If you look at things like hurricanes, and other meteorological disasters, they’re increasing in magnitude, so their damage is increasing. And also the frequency is increasing, meaning the gap between them is getting shorter so that local governments have less capacity. They [might be] dealing with Disaster 1 and Disaster 2 at the same time. So that’s absolutely true.

We need a new 21st century structure for handling these new, more regular and stronger disasters. How will we handle the costs of climate change? We spend way too much money after the fact and not enough money before the fact. The idea that we should be building resistance to a shock is a very powerful one that we don’t do very well. Typically, we spend all the money, again, in election years and after the disaster.

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings