The disaster effect

Politics tamfitronics

Hello, and welcome back to State of Emergency. My name is Zoya Teirstein. There is quite a bit of research on the politics of disasters and how extreme weather shapes voter behavior. We’ve cited some of it in this newsletter. Today, you’ll hear about that research through a different lens: from a researcher whose career, and life, was turned upside down by one of the deadliest disasters in American history.

In the spring of 2005, Daniel Aldrich was finishing his doctorate in Japanese energy politics at Harvard University. That summer, he moved to Louisiana with his wife and two young children, renting a house in New Orleans to begin his first-ever job in academia at Tulane University. The campus was abuzz in late August as students moved into their dormitories and teachers prepared for the first day of classes. The last Monday of that month was supposed to be Aldrich’s first day of teaching. He never made it to campus. Hurricane Katrina hit southeast Louisiana as a Category 4 storm the morning of August 29, 2005, leading to more than 1,500 deaths in three Southern states and causing $300 billion in damages.

The front of Daniel Aldrich’s rented house, located eight blocks from Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans, after it was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Courtesy of Daniel Aldrich

Twelve feet of water turned Aldrich’s house, eight blocks from Lake Pontchartrain, into a swamp, destroying everything he owned, including his car. The Aldriches evacuated to Texas first, then moved back to Boston. They didn’t go back to New Orleans for months, until that January. “That’s when we saw the on-the-ground horrors,” Aldrich said. On the walk from his house uptown to Tulane, little springs of water would shoot up out of the ground every few steps. The weight of the floodwater had crushed the city’s underground infrastructure. Finding a doctor was next to impossible. Grocery stores weren’t stocked. Abandoned boats blocked the streets. They didn’t last more than half a year. Aldrich got a job in Massachusetts, and the family went north again. In Boston, Aldrich’s children were tested for lead, a city requirement. Levels of the toxic metal in their blood had tripled while they were in New Orleans, where floodwater and post-hurricane demolition had sent the lead in the paint coating many of the houses in the city swirling into the environment.

“Hurricane Katrina destroyed my home, my car, and everything that I owned. For me, it certainly changed my perspective.”

— Disaster researcher Daniel Aldrich

Katrina marked a turning point in Aldrich’s life, and in his professional trajectory. He would spend the next two and a half decades researching the politics of disasters and disaster resilience, writing three books on the subject and becoming one of America’s foremost disaster resilience experts. And he would soon find that epochal disasters like Katrina are radicalizing — often representing an individual’s first interactions with the federal government. That experience, his research has found, can end up dictating political preferences and voter behavior.

Most importantly, Aldrich learned that survivors tend to become more civically engaged post-disaster: They run for office, start community groups, and show up at town meetings. Aldrich, used to sitting outside of the research he was conducting, realized that he had become a data point himself. “Hurricane Katrina destroyed my home, my car, and everything that I owned,” he said. “For me, it certainly changed my perspective.”

Read my full conversation with Aldrich here.

Follow the money

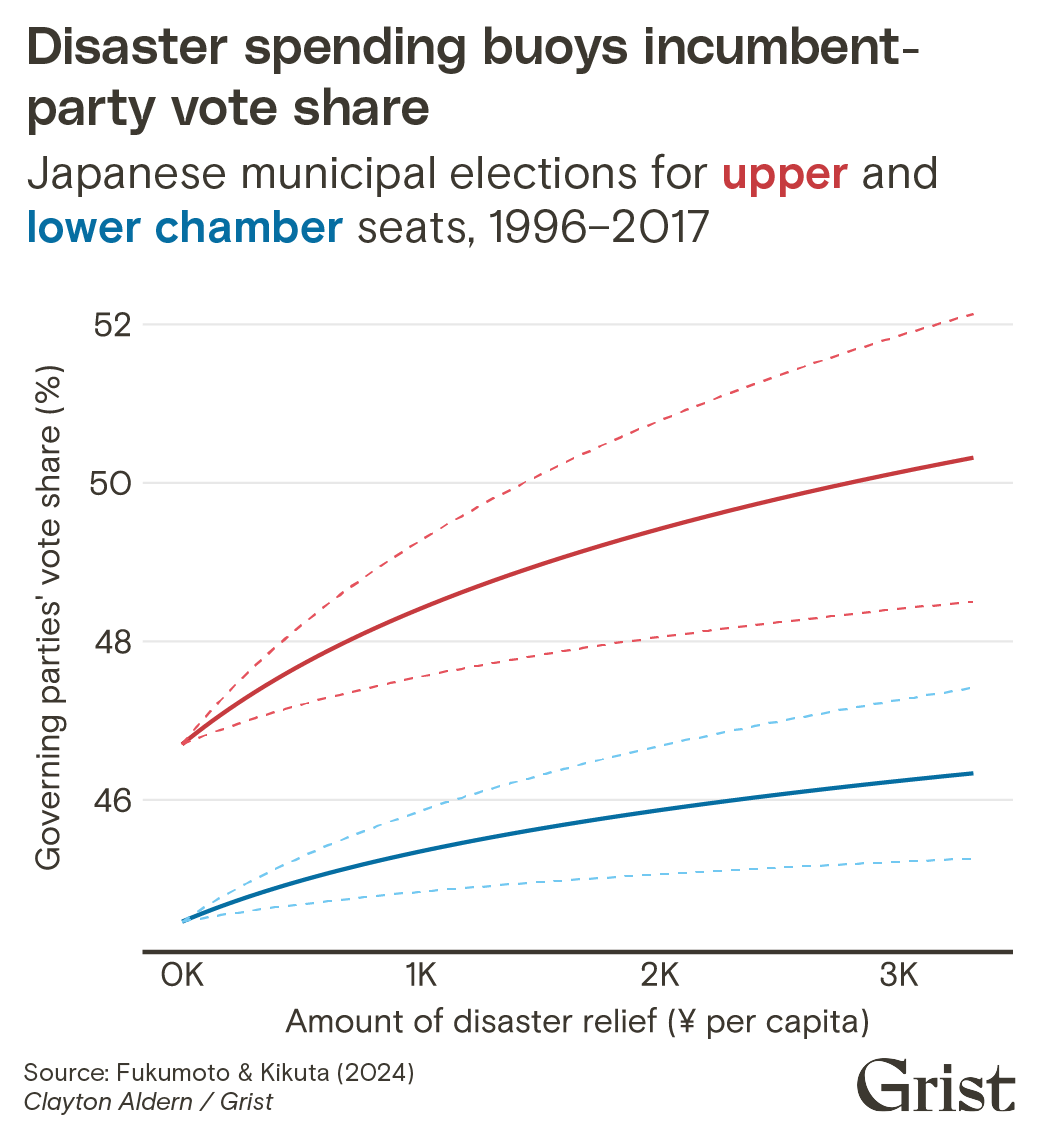

Researchers in Japan analyzed the effects of disaster relief on the electoral outcomes of incumbent parties. Decades of data revealed that electoral goods doled out in response to extreme weather events before elections can lead to statistically significant electoral gains for the party in power. We’re talking a bump of a few percentage points — 2.8 and 5.4 points for Japan’s lower and upper legislative chambers, respectively — but in my conversation with Aldrich, he pointed out that because just a third of eligible voters typically turn out to vote, a change of 2 to 5 percent is “a pretty big deal.”

What we’re reading

As PA chooses the next president, its unions are choosing clean energy: A coalition of trade unions have launched a new advocacy group, Union Energy, to ensure that Pennsylvania’s workers get a “just transition” to a fossil-fuel-free economy. My colleague Gautema Mehta reports on unions in the state, which is the nation’s second-largest producer and exporter of fuels for energy.  Read more

Read more

1 in 4 homeowners financially unprepared for the costs of extreme weather: As major insurance companies pull back coverage in flood- and fire-prone areas, a survey conducted by Bankrate, a financial services company, finds that 26 percent of homeowners fear they can’t afford the costs of climate-driven disasters. Another 15 percent of the 1,300 homeowners surveyed said they would go into debt just covering the deductible on their insurance policies.  Read more

Read more

10 tough climate questions for the presidential debate: Journalists at Inside Climate News have 10 climate questions for Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, who are preparing for their first head-to-head debate in Pennsylvania tonight. Climate change and extreme weather rarely get airtime during presidential debates. Inside Climate has the questions climate-conscious voters wish moderators would ask the candidates.  Read more

Read more

Washington state to reconsider its landmark climate program: In 2021, Washington lawmakers passed a cap-and-invest program, modeled after California’s carbon market, aimed at reducing emissions 45 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. In November, voters in the Evergreen State will vote on a measure that would repeal that program. Politico reporters interviewed the Democratic state senator fighting to keep it alive.  Read more

Read more

Extreme heat strains the power grid and causes outages through LA County: Triple-digit temperatures in California are setting records and leading to grid failures throughout Los Angeles County and other parts of the state. Thousands of customers in Los Angeles and in the neighborhoods surrounding the University of Southern California lost power. Meanwhile, in Oregon, several school districts canceled classes and reassessed the efficacy of their cooling systems due to high temperatures.  Read more

Read more

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings