In black and red: 75 years of the DMK

Politics tamfitronics

“The DMK, which split from the DK, redirected mass Dravidianism from a politics of heresy to a politics of community. Central to this change was the fuller incorporation of early Dravidianism’s essentialized ethnic categories within a popular discourse, which inspired the mobilisation of a broad coalition spanning the intermediate and lower strata.” — Narendra Subramanian in Ethnicity and Populist Mobilization, OUP, 1999.

It is the element of a “broad coalition” that has been a key feature of the DMK and this, among others, has kept the party going for 75 years. In all likelihood, it will continue to be so in future. A product of social and political changes that Tamil society witnessed in the later part of the 19th Century and the early years of the 20th Century, the organisation, seen at one stage as an extreme, mass communal force, has grown into a body that has learnt the art of moderation deftly.

A dominant Congress

When the DMK emerged on the political scene in September 1949, the Congress was the dominant force. Despite K. Kamaraj being the unquestioned leader of the Congress and hailing from an intermediate community, the DMK, in the initial years, targeted its adversary as a tool of Aryan or north Indian domination, a line of thinking pursued by Dravidar Kazhagam (DK) founder E.V. Ramaswami (EVR) immediately after he quit the Congress in the mid-1920s. Though the Dravidian major has a record of having opposed concepts such as varna and jaati [caste]it cannot be described as an organisation that adhered to atheism. Ably guided by EVR’s former lieutenant C.N. Annadurai, the party declared even in its initial years that it subscribed to the policy of “Ontre Kulam Oruvane Devan [One race, One god]”. This did not and does not mean that the party was or is free of atheists; but, as articulated by Annadurai, its position can be summarised as follows: neither break the Pillaiyar idol nor break the coconut to make an offering. Believers in the party are no longer considered undesirable persons. In fact, in the government of Chief Minister M.K. Stalin, there are at least a couple of Ministers who do not hesitate to display their religiosity. A few weeks ago, it hosted a conference on Lord Murugan in Palani.

In 1953-54, the party played an important role in the campaign against the Congress government’s variant of vocational education, dubbed as “kula kalvi thittam (caste-based educational system)”. Eventually, the then Chief Minister, C. Rajagopalachari, had to resign. Even as the DMK demanded a separate state — Dravida Nadu — till January 1963, it went on to hold a series of agitations, centring around language and culture. In the words of Robert L. Hardgrave, a prominent American political scientist who specialised in Tamil Nadu politics, (as reflected in an article in Pacific Affairs in the mid-1960s), the party had used the symbols of common culture within Tamil Nadu, harking back to the glories of the Dravidian past. In 1957, it entered the electoral fray for the first time, recording a modest success.

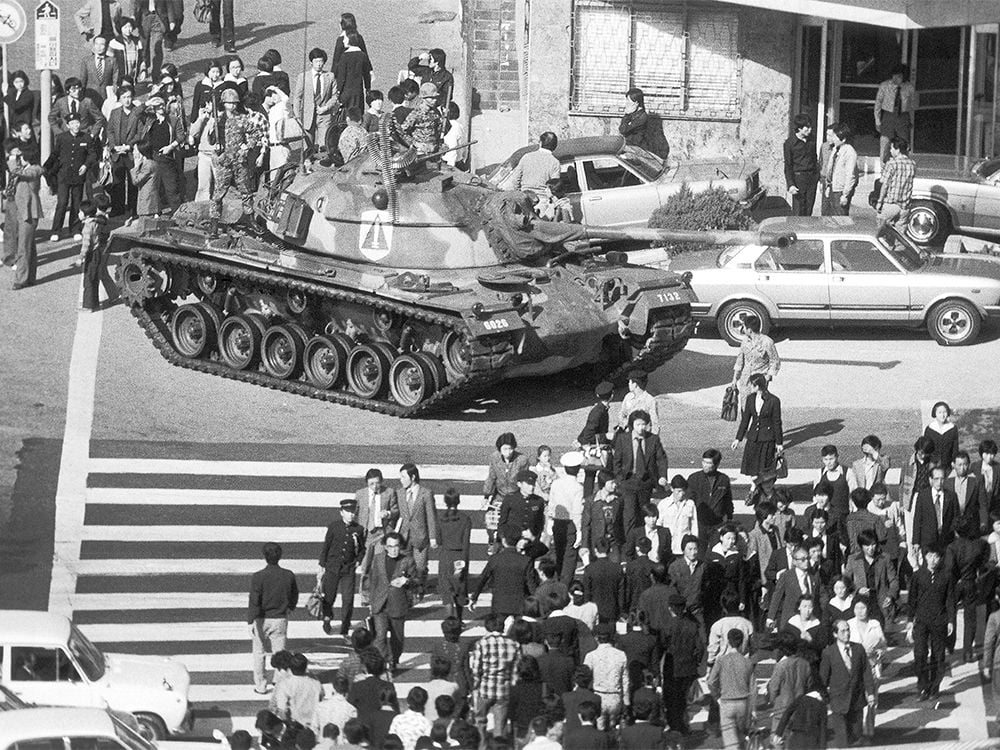

Agitation against Hindi

The anti-Hindi programme peaked in 1965 when the Union government wanted to fulfil the constitutional requirement of changing the country’s official language from English to Hindi. This came in handy for the DMK. Lack of imagination on the part of the Congress in handling the situation led to a serious law and order crisis in the State. The back-to-back failure of the southwest monsoon resulted in an acute shortage of foodgrains all over the country, increasing the dependence on food imports. Rajagopalachari, who became by then the Congress’s bitter critic and was running the Swatantra Party, and Annadurai stitched up an alliance that included the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and the Muslim League.

Meanwhile, the party’s strategy of employing the services of Tamil actors began paying off. Annadurai and his successor, M. Karunanidhi, themselves were the scriptwriters for many films. M.G. Ramachandran (MGR) and S.S. Rajendran had become active members of the DMK. This development took place despite the organisation having a number of orators. V.R. Nedunchezhiyan, who was the deputy to Annadurai, Karunanidhi, MGR, and Jayalalithaa in all their Cabinets, was among those who relentlessly toured all over the State to popularise the DMK’s policies, especially before 1967. On the eve of the Assembly election that year, an attempt on MGR’s life had generated sympathy for the party, which knocked the Congress out of power. Inexplicably, Kamaraj, who quit as Chief Minister in October 1963 to become the national president of his party, had contested in Virudhunagar, only to lose to a student leader, P. Srinivasan. Thus began the DMK’s spell in power which is continuing today, though there were gaps, including two separate periods of a decade-long uninterrupted rule of the AIADMK. Annadurai’s stint as the Chief Minister was short, but he created the impression of being an humane administrator.

In sync with the spirit of the times

V. N. Swami, a 94-year-old journalist who had once worked as a personal assistant to EVR, describes legalising “self-respect and secular marriages” between two Hindus during Annadurai’s rule as one of the achievements of the party. When Karunanidhi was the Chief Minister, the party’s concern for the poor was evident from the replacement of hand-rickshaws with cycle-rickshaws, the provision of incentives to those who had inter-caste marriages, and the implementation of housing schemes, he adds. A Tamil writer-thinker is full of appreciation for the current government’s schemes such as Pudhumai Penn and Mahalir Urimai Thogai, aimed at helping women financially. On the economic front, just as the DMK was in sync with the spirit of the times during the pre-liberalisation era, it remains quick to respond to the situation after economic reforms were launched.

The party has had its share of minuses. Once an opponent of “dynasty politics”, it has become a practitioner of such politics. Its governments were dismissed twice — on corruption charges in 1976 and for supporting the LTTE in 1991. On both occasions, Karunanidhi was the Chief Minister. When MGR and Jayalalithaa became his chief adversaries at different points of time, the DMK’s initial response was one of being dismissive of them. It cost the party dear. The DMK government’s approach towards the final phase of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009 is still held against the party.

A senior Minister in the Stalin government says his organisation has “not deviated” from its broader goals, focusing on matters such as the two-language formula and social justice. However, the Minister does not gloss over instances of the party having been “flexible” to stay afloat. Perhaps, the references pertain to the U-turns under the leadership of Karunanidhi, in ties with the Congress, headed by Indira Gandhi, between 1971 and 1980. Likewise, the DMK, once a bitter critic of the BJP, did not hesitate to join hands with it in 1999, and this relationship continued for over four years. In recent years, it seemed the BJP would become the DMK’s principal adversary, with the AIADMK’s meltdown. But the BJP-led front came a cropper in the 2024 Lok Sabha election, though it secured more than 18% of the votes polled. Yet, the Minister said he would not underestimate the AIADMK’s strength, calling it a “sleeping giant”.

In the years to come, the DMK will face new entrants, including actor Vijay’s party. It is aware of the changing situations, says the Minister, adding that it has to pay more attention to issues of livelihood that have a bearing on youth welfare.

Published – September 22, 2024 02:52 am IST

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings