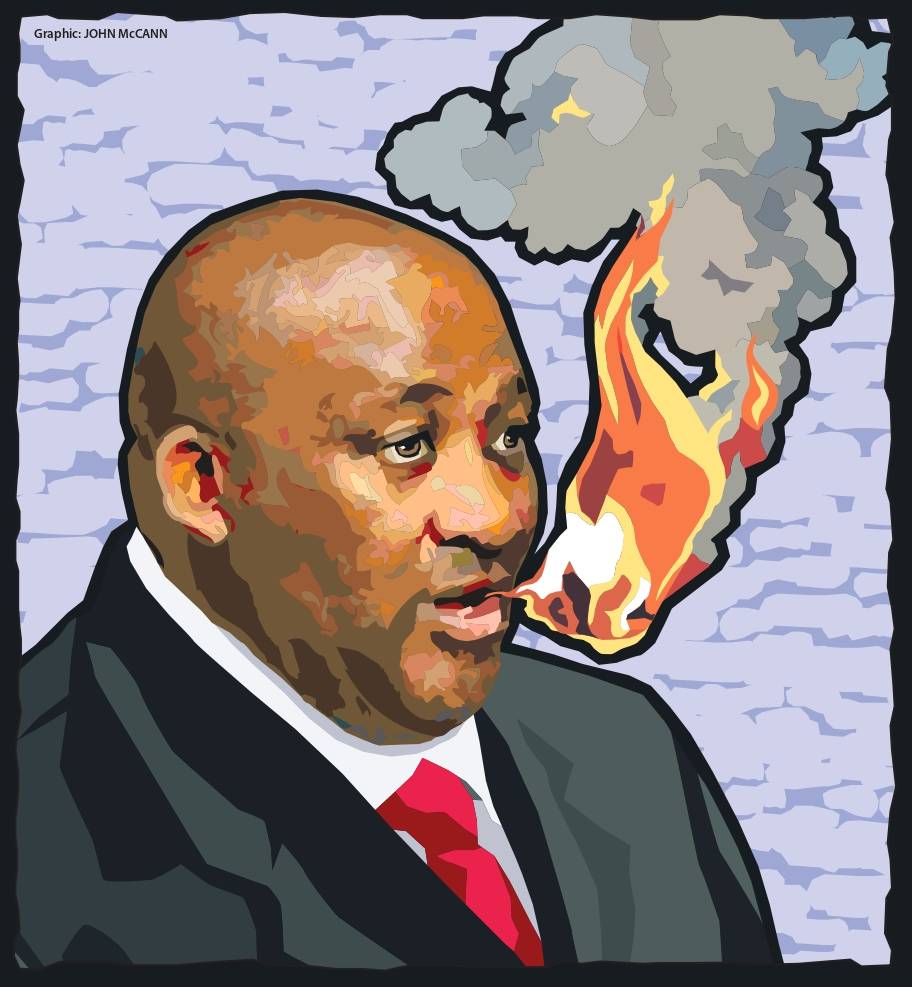

Gayton must go if GNU is to be credible

Politics tamfitronics

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

There is always a risk that national liberation struggles can abandon any meaningful idea of liberation and collapse into toxic forms of nationalism. Back in 1961 Frantz Fanon warned that nationalism can pass “to ultra-nationalism, to chauvinism, and finally to racism” with the result that “foreigners are called on to leave; their shops are burned, their street stalls are wrecked”.

Today xenophobia is central to right-wing politics in many countries. It is seldom solely a matter of hostility to migrants, and is generally entwined with other prejudices, with racism and Islamophobia being among the most common. The difference in how people fleeing the war in Ukraine and people feeling wars in Syria, Ethiopia, Sudan and Yemen have been treated in Europe makes this clear.

The cultivation of xenophobic sentiments has been the single most effective mechanism for right-wing forces to build the forms of reactionary populism that now threaten the integrity of a number of democracies.

In South Africa xenophobic hostilities are primarily directed at people deemed to have origins elsewhere in Africa, but people from Asia are also regularly subjected to xenophobic prejudice. When more than 500 people were displaced in xenophobic attacks in Makhanda, then known as Grahamstown, in 2015, the attacks were explicitly anti-Muslim in character and shopkeepers and others from a variety of countries in Africa and Asia were targeted, as well as one person from Palestine. There is also often a clear class dimension in terms of who is targeted.

Xenophobia is pervasive in our politics but has taken particularly crude and dangerous forms in the Patriotic Alliance, ActionSA and the uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) party, all of which take hard right positions on the question of migration and national identity, along with a number of other issues.

The first principle listed in the founding statement of intent by the government of national unity (GNU), initially affirmed by the ANC and the Democratic Alliance (DA), committed its participants to respect for the Constitution. This was how the line was drawn between the ANC, DA and a set of smaller parties on one side and the MK party and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and some smaller parties on the other.

The stated commitment to the Constitution was accompanied by a clear commitment to the Bill of Rights. In this spirit the founding statement also committed the government of national unity to human dignity, equality, justice, peace and active opposition to intolerance.

Some of the rights affirmed in the Constitution are specifically affirmed for citizens. These cannot be denied, limited or diminished on the grounds of ethnic or social origin, culture, language and birth. Others are not solely affirmed for citizens and although there is some room for debate about how this is parsed, it is clearly stated that when the Bill of Rights is interpreted the guiding principle must be an aspiration towards the realisation of “the values that underlie an open and democratic society based on human dignity, equality and freedom”. There is no constitutional sanction for dehumanising and abusing non-citizens.

McKenzie and the Patriotic Alliance are not the only participants in the unity government whose politics are at odds with those of the Constitution. Pieter Groenewald, of the Freedom Front Plus has, in the past, called for the reinstatement of the death penalty.

But Groenewald has accepted that the Constitution prohibits the death penalty and agreed to work within the parameters of the Constitution. He is not using his position as a cabinet minister to campaign for the reinstatement of the death penalty.

McKenzie and his party have long driven a xenophobic project using language, taking positions and acting in a manner that is directly opposed to the letter and spirit of the Constitution. Neither McKenzie nor his party have moderated this since their entry into the GNU. On the contrary, McKenzie and his party are using his position to actively oppose the values of the Constitution from the right.

Chidimma Adetshina has exactly the same rights as any other citizen to compete for the Miss South Africa title. When a young woman is subjected to an avalanche of online abuse, and instead of opposing that abuse, McKenzie, now a minister and therefore a powerful man, responds by saying that her presence gives him “funny vibes”, he is complicit with that abuse.

The Patriotic Alliance’s response was just as grim. The party issued a statement saying that “her family is fully Nigerian … and are celebrating her success as Nigerians not South Africans”. They also threatened to interdict the pageant organisers to have Adetshina removed.

Unfortunately the crudities of McKenzie and his party resonate with the general normalisation of xenophobic sentiment in parts of our society. Disregard for the legal fact of citizenship is rampant on social media and has become standard practice in much of the media. Citizens who are, correctly or not, deemed to have personal or familial origins outside of South Africa are regularly described and treated as “foreigners”, “foreign nationals”, “illegal immigrants” and sometimes as “criminals”.

During the ongoing public abuse of Adetshina many radio stations and online newspapers have run reports that present extreme xenophobic views, which in this case are also plainly both Afrophobic and gendered, as legitimate opinions, sometimes in the mode of cheerful vox pop. They would not do the same with regard to expressions of equally crude racism or homophobia.

As with all forms of prejudice, people animated by xenophobic hostilities like to claim that they are reasonable and realistic and that people who affirm equality are naïve. As is the case elsewhere in the world, elites in South Africa often try to legitimise their xenophobia by claiming that it emanates from the poor or working class, that it is an inevitable response to impoverishment and that out-of-touch liberals are adrift from reality.

This is self-serving nonsense. Like all forms of prejudice, xenophobia is a choice, a choice to scapegoat a vulnerable minority for social problems and a choice to take a sadistic pleasure in the diminution of the equal humanity of other people. It is, as Jean-Paul Sartre famously said of antisemitism, a passion.

There are people of all classes who embrace xenophobia and people of all classes who reject it. When Muslim migrants and their families were attacked in Makhanda in 2005, the Unemployed People’s Movement and the EFF opposed the attack.

There are migrants in positions of leadership in the industrial unions. Abahlali baseMjondolo also has migrants in leadership, works with migrant groups and explicitly makes opposition to xenophobia a condition of entry into the movement.

No deviation from the axiomatic affirmation of universal equality is ever justified. But refusing to accept that there can be any basis for denying the equality and equal right to dignity of any group of people is not solely a matter of refusing the politics of sadism out of compassion for its victims.

When we choose to see the migrant as an illegitimate interloper, or fail to understand that all countries have always included people with roots in other countries, we don’t only wound others by denying their equal humanity. We also debase ourselves and compromise our own humanity. We render ourselves ugly, as ugly as Trump, Marine le Pen, McKenzie and all the rest. Every time we acquiesce to the idea that some people should count for less than others we do not only debase ourselves. We also reinforce the idea that some people can be treated as less than others, an idea that enables all kinds of modes of exclusion, domination and abuse, many largely directed at people whose South African identity is never questioned.

When McKenzie and the Patriotic Alliance were brought into the government of national unity, all its participants knew that they were right-wing populists whose xenophobia was openly at odds with the Constitution. The kindest interpretation of this decision is that it was assumed that McKenzie would, like Groenewald, accept conformity to constitutional values as the price of entry.

There are also less kind interpretations, including the view that it was simply a matter of opportunism.

Politics is often marked by ideological flexibility and the unity government may or may not prove to be concerned about sustaining the credibility of its claim to be an alliance of constitutionalists holding the line against the MK party and the EFF. But, for as long as it wishes to sustain this claim, it cannot credibly do so if the Patriotic Alliance is not removed from the GNU and McKenzie is not removed from his position as a minister.

Gayton must go.

Richard Pithouse is a distinguished research fellow at the Global Centre for Advanced Studies in Dublin and New York, an international research scholar in the philosophy department at the University of Connecticut and a research associate in the philosophy department at the University of Johannesburg.

Discover more from Tamfis Nigeria Lmited

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings