Is the world order on the cusp of change?

Politics tamfitronics

“Asia-Pacific leaders will discover – as Australians are finding with Aukus – that the price for being deputy sheriff to the US will cost them and the coming generation more than just an exorbitant monetary sum.”

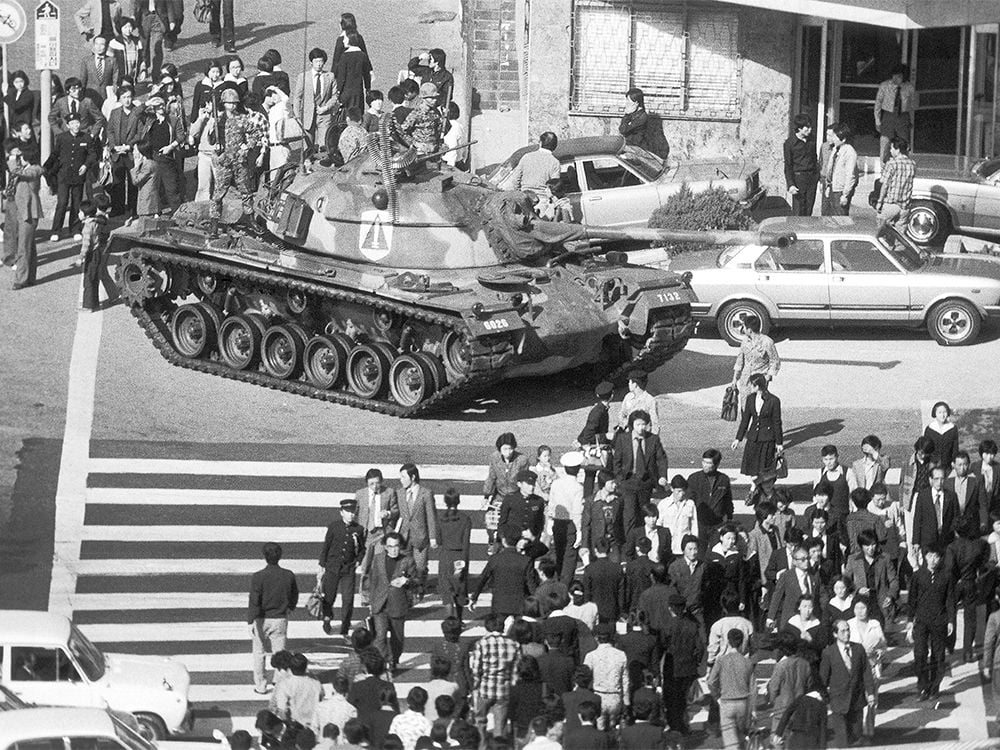

WITH Western mainstream media fixated on the US presidential election, they are critically missing examining the unprecedented turbulence rocking key players in geopolitics and the world order dominated by the United States.

The Group of Seven (G7) advanced economies forum, which has been coordinating global policy for 50 years and functioned as a handmaiden of American economic and foreign policy interests and agenda, is in disarray.

Italy has a newly elected president from the radical right wing, and its nationalist conservatism wave, anti-incumbency, anti-immigrant sentiments and electoral volatility have had aftershocks reverberate across the continent.

Today, France and Germany, the leading European nations, are having the grip of long-running establishment parties not just challenged but also considerably loosened.

Emmanuel Macron is virtually a lame-duck president for the next three years with diluted powers in domestic and foreign policy.

A similar fate awaits Olaf Scholz. Although not due for a leadership challenge soon, Scholz is in charge of a coalition government, which has turned further right and splintered more during the recent European parliament election.

Meanwhile, in Japan, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has booted himself out of his leadership position in government and his party.

Faced with a lacklustre economy, endemic political and money scandals, and equally unpopular ruling government and opposition parties, Japan is stalled for the foreseeable future with weak factionless leadership lacking strong majority support.

Rudderless in domestic politics, Japan has become more dependent on the US for foreign policy leadership. This is clear by its break from a more pacifist foreign policy to one with a record military expenditure for 2024, which is slated to increase until 2027.

Besides greater convergence with the US and its allies’ policy in the Asian region aimed at containing and contesting China, the Japanese government is now loosening export restrictions on the supply of complete lethal weapons and munitions to other countries.

What happens after November

As with G7’s malaise, whether it is Donald Trump or Kamala Harris winning the presidential election, he or she will have to prioritise the domestic issues dividing the country, and which their respective parties and political leaderships have been unable to deal with.

Better jobs, inflation, immigration, race, abortion, healthcare, Supreme Court and justice, crime and gun control – the blend and interplay of sociocultural, economic and political homegrown problems and concerns have become mainstream.

They have also grown steadily more toxic and unresolvable. Whoever wins, however large the margin and whatever the feel good cheerleaders in the media and think tanks may have to say in the election aftermath, US society – post-election – will remain polarised and disunited with Republicans and Democratic leaders and voters standing firm and unyielding on opposite sides on major domestic issues.

Meantime, the polls tracking American trust in government, which go back to 1958, are at or near record lows. As of April, an overwhelming minority 22% of Americans say they trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” (2%) or “most of the time” (21%).

Last year, 16% said they trusted the government just about always or most of the time, which was among the lowest measures in nearly seven decades of polling.

What is also significant is that there is little trust in most of the major US institutions. Whether it be the presidency, Congress, judiciary, medical system, the Church and organised religion, banks, police, public schools, newspapers and television news, etc, American public trust in the institutions that are the hallmark of their way of life has plummeted to levels that resemble those of the “failed” states that admirers of the US are prone to referring to when targeting countries with criticism.

If US leaders cannot inspire trust in their institutions or provide confidence to their own public, what is it that we can expect from them to inspire and sell to their allies and the rest of the world?

For now, there should be no illusion that the US – through the enormous resources, reach and primacy of its military, industrial, commercial, media and academic complex (MICMA) and the support of its deputy sheriffs in allied countries – will continue being the chief instigator and perpetrator of wars, military conquest, gunboat diplomacy, unequal treaties, economic exploitation, sanctions and other dirty tricks.

We can expect it to be business as usual for America’s MICMA and its junior members, now including Japan, especially at the weapons-selling table. Unfortunately, they are being joined by other countries in the lucrative weapons market.

Pay up or else

There will be one important difference though for G7 and Nato (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) members arising from the US presidential outcome.

Whoever wins will insist that member countries will have to cough up and pay a lot more given the distressed state of the US national debt which recently hit a record US$34 trillion (RM160.48 trillion), and the huge annual deficit of over US$1.5 trillion so far for 2024.

According to a Le Monde report, “Why did Donald Trump accuse Nato members of not paying?”, Trump noted: “I said, ‘You didn’t pay, you’re delinquent. No, I would not protect you. In fact, I would encourage (the Russians) to do whatever the hell they want’.”

The UK Guardian quoted the following: He (Trump) recounted a conversation with an unidentified Nato member in which he said, “You didn’t pay? You’re delinquent? No, I would not protect you. In fact, I would encourage them to do whatever the hell they want. You gotta pay. You gotta pay your bills.”

Trump’s running mate, J.D. Vance has been equally forthright and has declared: “No more free rides for nations that betray the generosity of the American taxpayer.”

He also warned: “(We) will send our kids to war only when we must.”

It is more than likely that the administration of Harris if she wins will take the same position as Trump in demanding that Nato and other US allies pay a great deal more to secure the “privilege” of American protection.

G7 and Nato citizenry perhaps can console themselves that this insistence by the US that it will no longer be the major paymaster of Nato may have a positive counter effect on their foreign policy allegiance and dependence on the US.

This may even provide a first step to the end of the war in Ukraine, and help bring genuine peace and security to the continent.

Asia-Pacific leaders should take notice too. What G7 and Nato members will have to deal with in financial year 2025 onwards will have to be reckoned for in the defence budgets in Australia, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines, where some of the over 750 military bases of the US around the world are located.

They will find, as Australians are belatedly finding with Aukus, that the price they have to pay for being deputy sheriff to the US will cost them and the coming generation an exorbitant sum, and this does not include the consequences of being party to a war over which they will have no control and from which there will be no victors.

Lim Teck Ghee’s Another Take is aimed at demystifying social orthodoxy. Comments: [email protected]

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings