Beyond the gender gap: Presidential politics is a ‘masculinity contest’

Politics tamfitronics

In the United States, women have, for decades, tilted toward Democrats, who today are leaning into issues like abortion access and economic equality. Men have leaned toward Republicans, who are evoking traditional gender roles in discussing gun violence, child care, and family planning.

But this campaign underscores a preference – beyond gender – for masculinity in the nation’s highest office, says Lindsey Meeks, a University of Oklahoma professor specializing in political communication and gender: “It doesn’t have to necessarily be a man, but [voters are] still really liking a masculine presence at that level.”

Politics tamfitronics Why We Wrote This

The gender gap in U.S. presidential politics is not new. But in this election year, the importance of projecting power has become gendered. Both candidates are wooing voters with their own brands of masculinity.

Former President Donald Trump’s campaign displayed hypermasculine images. From appearances with pro wrestlers to frequent use of aggressive language, he has connected with male voters who value a certain type of masculinity.

Vice President Kamala Harris walks a finer line, attempting to appeal to men while keeping her base among women. She’s played up her more masculine qualities – as California’s “top cop” and as a gun owner.

“Almost every election is, in fact, a masculinity contest,” says Dan Cassino, executive director of polling at Fairleigh Dickinson University. “To be taken seriously as a potential leader, you have to show masculine traits.”

As early voting gets underway across the United States, one political divide has become clear: Most men prefer former President Donald Trump. Most women prefer Vice President Kamala Harris.

That gap reflects party narratives throughout this election season – with Democrats leaning into issues like abortion access and economic equality, while Republicans have evoked traditional gender roles in discussing gun violence, child care, and family planning.

This gender gap, while significant, goes back decades. What this campaign underscores is Americans’ broader preference – beyond gender – for masculinity in the nation’s highest office.

Politics tamfitronics Why We Wrote This

The gender gap in U.S. presidential politics is not new. But in this election year, the importance of projecting power has become gendered. Both candidates are wooing voters with their own brands of masculinity.

The president “doesn’t have to necessarily be a man, but [voters are] still really liking a masculine presence at that level,” says Lindsey Meeks, a University of Oklahoma professor specializing in political communication and gender.

Politics tamfitronics Power projection

Trump stumper Tucker Carlson at a rally this week implicitly referred to his presidential candidate as “Dad.” He unfurled a metaphor in which “when Dad comes home” he deals with his misbehaving children – implicitly the Democrats: “You’ve been a bad little girl, and you’re getting a vigorous spanking.” It capped a campaign laden with hypermasculine images. From appearances with pro wrestlers to frequent use of aggressive language – including a recent vulgar reference to the late golf legend Arnold Palmer’s anatomy – former President Trump has consistently connected with male voters who value a certain type of crude masculine power figure. And Friday he is set to record an interview with Joe Rogan, the podcaster wildly popular with young male audiences, including young Black men.

Julia Demaree Nikhinson/AP

Cheering supporters of former President Donald Trump wait for him to take the stage at a campaign rally this week in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Ms. Harris is walking a finer line, attempting to appeal to men while keeping her base among women. Her choice of Tim Walz as a running mate brought some balance to her femininity. But she’s also played up her more masculine qualities – as California’s “top cop” and as a gun owner. And, this week, former President Barack Obama rallied supporters on her behalf in Detroit alongside rapper Eminem, making a pointed appeal to young men to support the Democratic candidate.

Projecting strength is trickier for women, says Dan Cassino, who conducts polling for Fairleigh Dickinson University. “Female candidates have to be masculine, but not too masculine, and feminine, but not too feminine. Whereas masculine male candidates just have to be masculine.”

Recent polling he has conducted illustrates those differences: Among registered voters, 41% say Mr. Trump is “completely masculine.” Of that share, 84% say they’re going to vote for him. Some 54% say Ms. Harris expresses some degree of masculinity.

“Almost every election is, in fact, a masculinity contest. We just don’t see it because it’s [been] just two men,” he says. “To be taken seriously as a potential leader, you have to show masculine traits.”

The audience at a Democratic campaign rally listens to vice presidential nominee Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz in Papillion, Nebraska, last Saturday.

Politics tamfitronics Bold lines along the gender divide

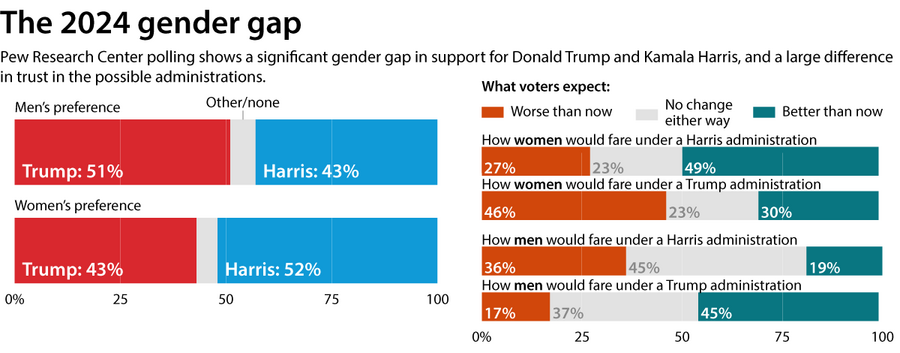

The division along gender lines is stark: In a Pew Research Center survey this month, 51% of men and 43% of women lean toward supporting Mr. Trump. Ms. Harris has the mirror image of that support – 52% of women and 43% of men prefer her candidacy.

Another Pew survey shows some voters believe those candidates’ policies would benefit their corresponding gender – and harm the other. Among registered voters, nearly half say a Harris presidency would help women, while 36% believe it would make things worse for men; 45% say a Trump win would make things better for men, and 46% say it would be worse for women.

SOURCE:

Pew Research Center

|

Jacob Turcotte/Staff

This polarity reflects ways in which the two political parties have solicited support for their respective platforms: Republicans have doubled down on gender stereotypes, while Democrats, until recently, have centered their messaging on issues important to women and racial minorities.

Lost in this political gambit, say some experts, are the real needs of contemporary men and boys.

“The main sound on issues of boys and men from the Democrats until very, very recently in the race has been the sound of silence,” says Richard Reeves, founder and president of the American Institute of Boys and Men. “Whereas on the Republican side, there’s been a lot of talk and a lot of performance.”

Both parties are treating gender issues as a zero-sum game, says Mr. Reeves, adding, “I don’t think it’s good in the long run to have a men’s party and a women’s party. I think we do have to rise together.”

A child sports a hat supporting Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump. She – and Mr. Trump – were attending a campaign event this week in Duluth, Georgia, sponsored by the conservative student group Turning Point USA.

A large draw for women to the Harris ticket has been the Democratic position on abortion access and other fertility-related options, says Dr. Meeks. Men tend to be more hawkish than women on defense and international relations – and they’re more likely to be threatened by a Harris-Walz ticket that inverts historical gender norms. She adds, “You could see any of those levers pushing [men] towards Trump over Harris.”

Politics tamfitronics Changes for men, and the politics of empowerment

That’s not to say all men – or women who depend on male success for their economic security – don’t support women’s issues. But the rise of women’s earnings and subsequent choices in recent years has made men less of an economic necessity for women, say experts.

“That is an amazing economic liberation and exactly what the women’s movement was about in that way,” says Mr. Reeves. But this liberation for women has presented a difficult transition for men, who face their own issues, including higher suicide rates and lower high school graduation rates than women, and other pressures related to working and making money.

Republicans have tailored their messaging to acknowledge men in ways that Democrats have not, says Mr. Reeves. “The basic underlying [Republican] message is ‘We are guys. We like guys. And we like the things that guys like.’ And so that’s a strong cultural message from the right.”

But the contrasting messages around gender may have eroded the party’s stronghold among Black men, while another reliably Democratic bloc – Hispanic voters – is also shifting toward Mr. Trump. With the presidential race in a statistical dead heat, every vote matters. And the Harris camp is working to broaden its appeal – ramping up its pitch to men while continuing to double down on issues that appeal to its current base, like abortion and equality.

“The Harris campaign is trying to talk to men around issues of the economy, talking about small businesses, talking about the kind of an economy of opportunity,” says Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women in Politics at Rutgers University. “But they’re also very much hoarding that women’s vote. I think there’s no question that they’ve read the memo that women voters really matter.”

Indeed, more women than men tend to vote. In the 2020 election, it was 10 million more.

At the same time, says Mr. Reeves, “Republicans are doubling down on their identity as the men’s party, and [Republicans and Democrats] are just hoping to turn out enough on their side to counteract the loss.”