NASA data suggests there’s liquid water deep beneath Mars’ surface

NASA Space Technology

One of the prerequisites for life as we know it is liquid water—and there’s direct evidence of it having once existed on Mars. However, that was billions of years ago, and today the planet’s temperature is well below the freezing point of watermeaning that any water near or on the surface is almost certainly frozen solid.

However, a new study published August 9 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that there may be liquid water on Mars today—or, more accurately, in Mars. The study suggests that there’s liquid water deep, deep in the Martian crust—at least five miles down, and potentially as far as 15 miles.

This means that we’re unlikely to ever be able to study this water directly—as the notes accompanying the study’s release point out, even on Earth, drilling even a kilometer into the crust is extremely difficult. Even if the necessary equipment could be somehow transported to Mars, any drilling operation on the red planet would most likely be just as challenging, if not more so: as Michael Manga, one of the study’s co-authors, explains to Popular Science, “[Mars’s] low gravity might help a bit. But it takes lots of mass and energy to drill. [On Earth]we also normally circulate lots of fluid (water, mud) to help with the drilling. These would presumably have to be transported to Mars.”

It’s this sheer inaccessibility, however, that allows water to exist in liquid form in the first place. Manga says that the important factors are heat from the planet’s core and the ambient pressure: “At these depths, water would be liquid, not ice. Given what we expect for the heat flow coming out of Mars, the water would not be too hot, but the pressure would … keep it in liquid form.”

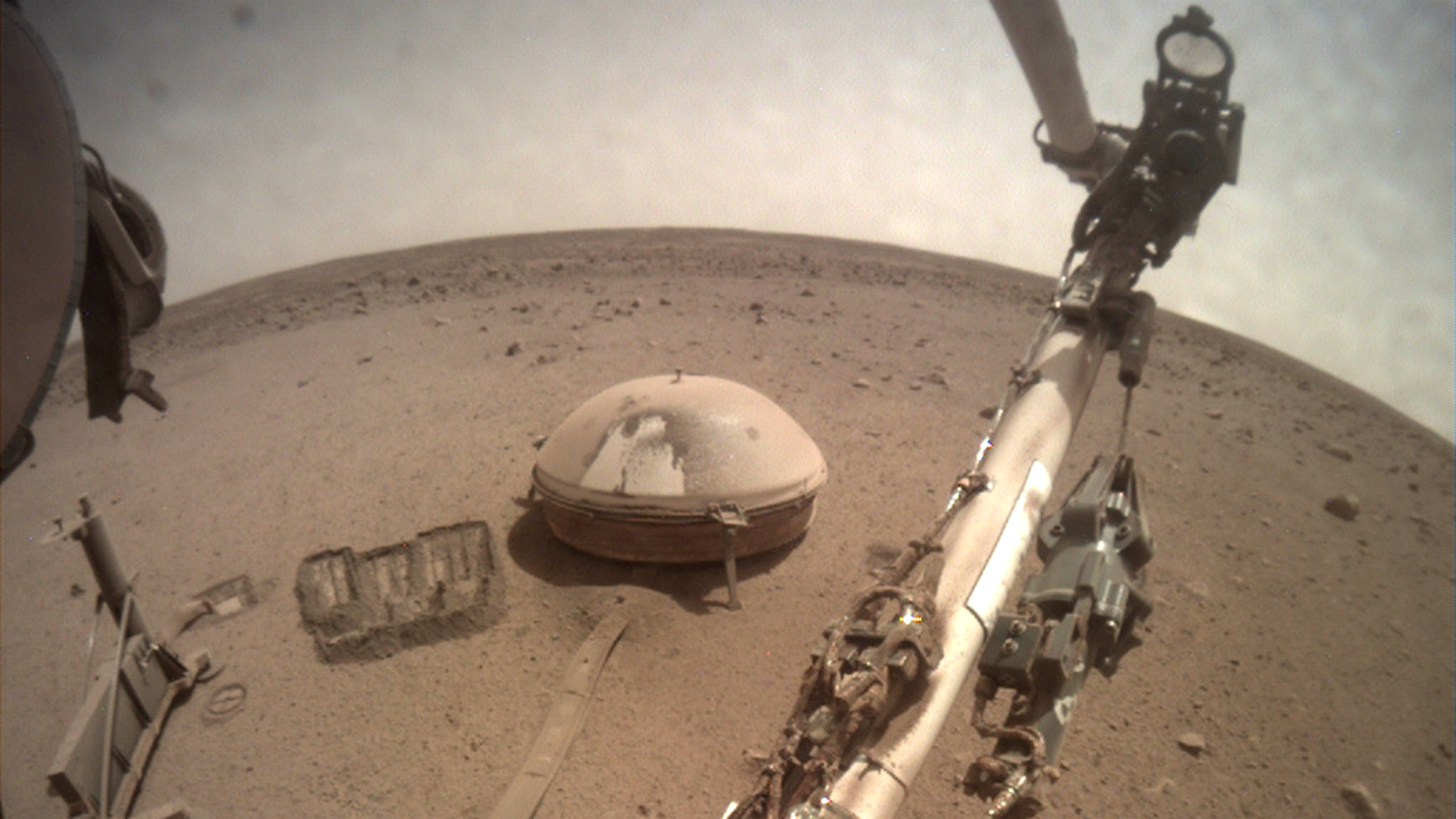

The study is based on data gathered by NASA’s InSight lander, which landed on the Martian surface in November 2018 and operated until late 2022. The lander gathered extensive information about Martian geology. Manga explains that this new data was crucial to his team’s approach: “The data from InSight was essential” to this work. “Beyond our study, it revealed that Mars is tectonically active [along with] the thickness of the crust and the size of the core.”

This information allowed the team to construct detailed models of the crust and the physics of its rock, examining multiple combinations of variables like lithology, water saturation, porosity, and pore shape in order to find the best fit with the data. Manga explains that this approach is “similar to that we use [on Earth] to search for oil and gas, or determine properties of aquifers.”

As the paper explains, the team’s results suggest that the InSight data is best explained by “a water-saturated mid-crust.” As Manga says, this doesn’t imply the existence of large bodies of water—he says that the mid-crust is best pictured as “a rock full of cracks, with those cracks filled with water.”

The presence of water deep in the Martian crust also raises the questions of how that water got there, and where it came from. Manga says, “On Earth, groundwater underground infiltrated from the surface and we expect this to be similar to the history of water on Mars.” As to where the water came from, this remains a subject for speculation, but Manga notes that “the crust on Mars could also have been full of water from very early in its history.”

Whatever the case, this is exciting news, because scientists have hypothesized that if life did evolve on Mars billions of years ago, some vestiges might remain in exactly the sort of aquifers that the study suggests do indeed exist deep in the Martian crust.

Hot Deals

Hot Deals Shopfinish

Shopfinish Shop

Shop Appliances

Appliances Babies & Kids

Babies & Kids Best Selling

Best Selling Books

Books Consumer Electronics

Consumer Electronics Furniture

Furniture Home & Kitchen

Home & Kitchen Jewelry

Jewelry Luxury & Beauty

Luxury & Beauty Shoes

Shoes Training & Certifications

Training & Certifications Wears & Clothings

Wears & Clothings