Health News tamfitronics

Charlotte, North Carolina. — Four months after seeking asylum in the United States, Fernando Hermida began coughing and feeling tired. At first he thought he had a cold. Then sores appeared in his groin and he began to soak his bed with sweat. A test was done.

On New Year’s Day 2022, at age 31, he learned he had HIV.

“I thought I was going to die,” she said, remembering the chill that ran through her body as she reviewed her results. He struggled to navigate a complicated new health care system. Through an HIV organization she found on the Internet, she received a list of medical providers in Washington, DC, where she was at the time. But they didn’t return his calls for weeks.

Hermida, who only speaks Spanish, didn’t know where to go.

By the time Hermida received her diagnosis, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) had been carrying out a federal initiative to end the nation’s HIV epidemic, investing hundreds of millions of dollars each year in certain states, counties and territories with the highest infection rates.

The objective was to reach approximately 1.2 million people living with HIV, including some who don’t even know it.

Overall, estimated rates of new HIV infections have decreased 23% from 2012 to 2022. But an analysis by KFF Health News and the Associated Press found that the rate has not decreased for Latinos (who can be of any race) as much. as for other racial and ethnic groups.

While African Americans overall continue to have the highest rates of HIV in the country, Latinos accounted for the majority of new HIV diagnoses and infections among gay and bisexual men in 2022, according to the most recent data available, compared to other racial and ethnic groups.

Latinos, who make up about 19% of the U.S. population, accounted for about 33% of new HIV infections, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The analysis found that Latinos are experiencing a disproportionate number of new infections and diagnoses nationwide, with the highest diagnosis rates in the Southeast.

Public health officials in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and Shelby County, Tennessee, where data shows diagnosis rates have increased among Latinos, told KFF Health News and the AP they have no plans specific to address the problem of HIV in this population, or that these have not yet been finalized.

Even in well-resourced places like San Francisco, California, HIV diagnosis rates have increased among Latinos in recent years while declining among other racial and ethnic groups, despite county goals to reduce infections among The latinos.

“HIV disparities are not inevitable,” Robyn Neblett Fanfair, director of the CDC’s Division of HIV Prevention, said in a statement. She pointed out systemic, cultural and economic inequities, such as racism, language differences and distrust in doctors.

And while the CDC does provide some funding for minority groups, Latino health policy advocates want HHS to declare a public health emergency in hopes of directing more money to Latino communities, arguing that current efforts are not enough.

“Our invisibility is no longer tolerable,” said Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, co-chairman of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

Lost without an interpreter

Hermida suspects that she contracted the virus while in an open relationship with a male partner before arriving in the United States. In late January 2022, months after his symptoms began, he went to a clinic in New York City that a friend helped him find to finally receive treatment for HIV.

Too sick to care for himself, Hermida eventually moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, to be closer to his family and in hopes of receiving more consistent medical care. He enrolled in a clinic Amity Medical Group which receives funding from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, a federal safety net plan that serves more than half of those diagnosed with HIV in the nation, regardless of their immigration status.

After he connected with case managers, his HIV became undetectable. But she said that, over time, communication with the clinic became less frequent and she did not receive regular help from an interpreter during visits with her doctor, who spoke English.

An Amity representative confirmed that Hermida was a client, but did not answer questions about her experience at the clinic.

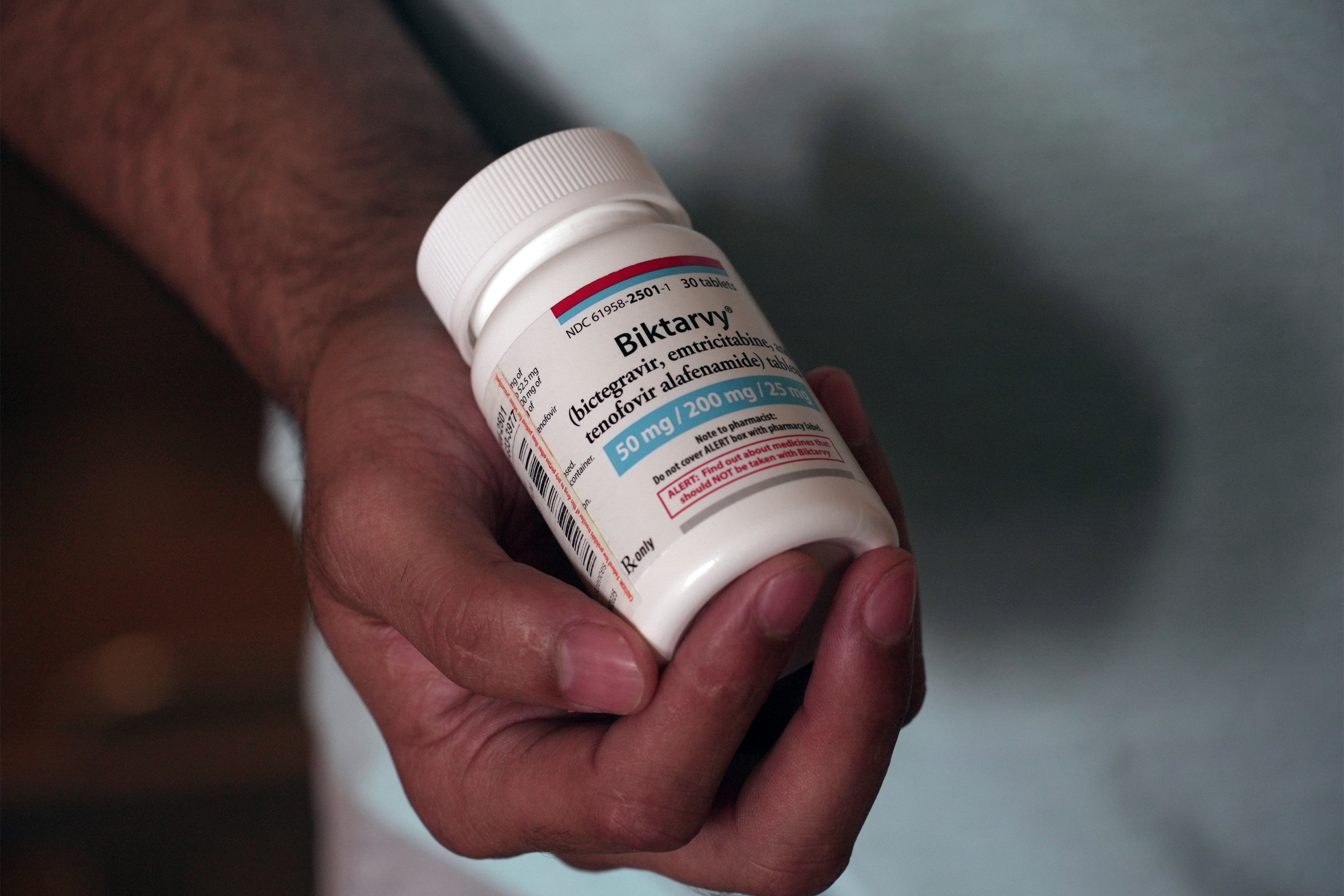

Hermida said he struggled to complete paperwork to stay enrolled in the Ryan White program, and when his eligibility expired in September 2023, he was unable to obtain his medication.

She left the clinic and enrolled in a health plan through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) insurance marketplace. But Hermida did not realize that the insurance company required him to pay a portion of her HIV treatment.

In January, the Lyft driver received a bill for $1,275 for his antiretroviral medication, the equivalent of 120 rides, he said. He paid the bill with a coupon he found online. In April, he received a second bill that he could not pay. For two weeks, he stopped taking the medication that keeps the virus undetectable, and therefore non-transmissible.

“I’m collapsing,” he said. “I have to live to pay for the medication.” One way to prevent HIV is pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, which is taken regularly to reduce the risk of contracting HIV through sex or intravenous drug use. Was approved by the federal government in 2012but adoption has not been uniform across different racial and ethnic groups: CDC data shows much lower PrEP coverage rates among Latinos than among non-Hispanic white Americans.

Epidemiologists say good use of PrEP and consistent access to treatment are necessary to build resistance at the community level.

Carlos Saldana, an infectious disease specialist and former medical advisor to the Georgia Department of Health, helped identify five rapid HIV transmission groups that involved about 40 gay Latinos and men who have sex with men from February 2021 to June 2022. Many people in the group told researchers they had not taken PrEP and found it difficult to understand the health system.

Saldana said they also experienced other barriers, including lack of transportation and fear of deportation if they sought treatment.

Latino health policy advocates want the federal government to redistribute funding for HIV prevention, including testing and access to PrEP. Of the almost $30 billion In federal money that went to HIV healthcare, treatment and prevention services in 2022, only 4% went to prevention, according to a KFF analysis.

Advocates suggest that more money could help reach Latino communities through efforts such as faith-based outreach in churches, testing at clubs during Latino fiestas, and in training bilingual staff to conduct testing.

Latino rates increase

Congress has assigned $2.3 billion over five years for the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative, and jurisdictions receiving the money must invest 25% in community organizations.

But this initiative does not require targeting certain groups, including Latinos: it delegates to cities, counties and states the task of devising specific strategies.

In 34 of the 57 areas receiving money, cases are trending in the wrong direction: Diagnosis rates among Latinos increased from 2019 to 2022 while declining in other racial and ethnic groups, the KFF Health News-AP analysis found.

Starting Aug. 1, state and local health departments will be required to submit annual spending reports on funding in settings that account for 30% or more of HIV diagnoses, the CDC said. Previously, this was only required in a small number of states.

In some states and counties, initiative funding has not been enough to meet the needs of Latinos. South Carolina, which saw rates among Latinos nearly double from 2012 to 2022, has not expanded mobile HIV testing in rural areas, where the need is high among Latinos, said Tony Price, HIV program manager at the department. of state health.

South Carolina can only afford four community health workers focused on HIV outreach, and not all of them are bilingual.

In Shelby County, Tennessee, home to Memphis, the HIV diagnosis rate among Latinos increased 86% from 2012 to 2022. The Department of Health said it received $2 million in funding from the initiative in 2023 and, although the county plan Recognizing that Latinos are a target group, the department’s director, Michelle Taylor, said: “There are no specific campaigns just among Latinos.”

Until now, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, has not included specific goals to address HIV in the Latino population, where rates of new diagnoses have more than doubled in a decade but declined slightly among other racial and ethnic groups. .

The health department has used funds for bilingual marketing and PrEP awareness campaigns.

Moving for medicine

When it was time for Hermida to pack up and move to her third city in two years, her fiancé, who is taking PrEP, suggested seeking care in Orlando, Florida.

The couple, who were high school friends in Venezuela, had some family and friends in Florida, and had heard about Pineapple Healthcare, a nonprofit primary care clinic dedicated to supporting Latinos living with HIV.

The clinic is in an office south of downtown Orlando. The staff, mostly Latino, wear turquoise T-shirts with pineapple prints, and Spanish is heard more often than English in the treatment rooms and hallways.

“At its core, if the organization is not run by and for people of color, then we are just an afterthought,” she said. Andres Acosta Ardiladirector of community outreach at Pineapple Healthcare, who ien was diagnosed with HIV in 2013.

“Did you move recently?” [mente]“Finally?” asked nurse Eliza Otero, who began treating Hermida when she still lived in Charlotte. “It’s been a month since we last saw each other.”

They still need to work on lowering their cholesterol and blood pressure, he told her. Although his viral load remains high, Otero said he should improve with regular, consistent care.

Pineapple Healthcare, which does not receive money from the federal initiative, offers comprehensive primary care primarily to Latino men. There, Hermida gets her HIV medication at no cost because the clinic is part of a federal drug discount program.

In many ways, the clinic is an oasis. The rate of new diagnoses for Latinos in Orange County, Florida, which includes Orlando, increased by about a third from 2012 to 2022, while it decreased by a third for others. Florida has the third largest Latino population in the United States and had the seventh highest rate of new HIV diagnoses among Latinos in the nation in 2022.

Hermida, who has his asylum case pending, never imagined getting medication would be so difficult, he said during the 500-mile trip from North Carolina to Florida. After hotel rooms, lost jobs and family goodbyes, she hopes his search for consistent HIV treatment, which has defined his life for the past two years, can finally come to an end.

“I am a nomad by force, but well, as my fiancé and my family say, I have to be where I get good medical services,” he said.

That is the priority now, he added.

KFF Health News and The Associated Press analyzed data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the number of new HIV diagnoses and infections among Americans ages 13 and older at the local, state and national levels.

This story primarily uses incidence rate data — estimates of new infections — at the national level and diagnosis rate data at the state and county levels.

Bose produced this story from Orlando, Florida. Reese, from Sacramento, California. Video journalist Laura Bargfeld contributed to this report.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. AP is responsible for all content.

This story was produced by KFF Health Newswhich publishes California Healthlinean editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Health News tamfitronics A project of KFF Health News and The Associated Press

Co-published by Univision News

Health News tamfitronics CREDITS

Reporters:

Vanessa G. Sanchez

Devna Bose

Phillip Reese

Cinematography:

Laura Bargfeld

Photography:

Laura Bargfeld

Phelan M. Ebenhack

Video Editing:

Federica Narancio

Kathy Young

Esther Poveda

Additional video:

Federica Narancio

Esther Poveda

Video production:

Eric Harkleroad

Lydia Zuraw

Publishers:

Judy Lin

Erica Hunzinger

Data editor:

Holly Hacker

Social networks:

Patricia Velez

Federica Narancio

Esther Poveda

Carolina Astuya

Natalia Bravo

Juan Pablo Vargas

Kyle Viterbo

Sophia Eppolito

Hannah Norman

Chaseedaw Giles

Tara Lofton

Translation:

Paula Andalo

Correction:

Gabe Brison-Woke up