Politics tamfitronics

After 55 years at The AgeMichael Leunig filed his final cartoon for the newspaper last week after he was fired by Nine in what he described as “a throat-cutting exercise”. The popular cartoonist has been declared an Australian Living Treasure, but has also drawn ire over the decades for various controversies including his critique of working mothers who use childcare and taking an anti-vaccination stance.

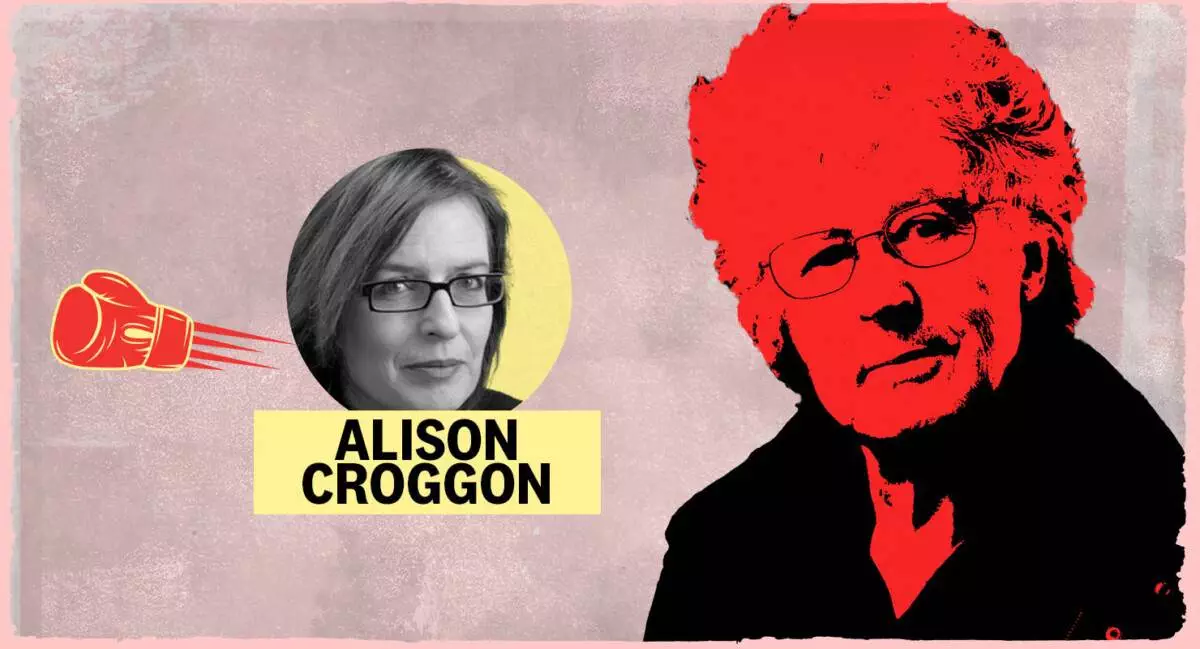

So should we mourn the axing of Michael Leunig? In today’s Friday Fight, former editor of The Age Michael Smith argues in the affirmative, and The Saturday Paper’s arts editor Alison Croggon argues in the negative.

I’m not sure that mourning is something anyone can compel or forbid. Mourning essentially isn’t a conscious decision: you grieve — or don’t grieve — involuntarily. Sorrow is a resonance of the soul, something that emerges from the depths of being. There’s no “should” about it.

Of course, mourning also has many public aspects. There is all the paraphernalia of the funeral, the formal ritual of laying a body to rest, which is more about those left behind to deal with incomprehensible loss and change. The desire to show respect towards someone who perhaps you didn’t know personally but whose passing touches you.

In any case, mourning seems a big verb to ascribe to the departure of Michael Leunig from his regular gig at The Age. After all, even though he was lucky enough to work there for 55 years, it’s not like he’s dead.

I’m of the generation that grew up with at least two or three dog-eared collections of Leunig in the bookshelf. My father — at the time a paid-up Liberal Party member — bizarrely subscribed to Nation Reviewa satirical publication that featured many of Leunig’s cartoons, among articles from Germaine Greer, Mungo MacCallum, John Lurie and many others. We all had those “innocent bystander” t-shirts. Nation Review turned up weekly in our mailbox until, after a particularly lubricious Bob Ellis film review that 10-year-old me read with pop-eyed fascination, it mysteriously stopped arriving.

At his best — when he managed to temper his tendency for saccharine whimsy with a razor-sharp wit — Leunig was a wonderful cartoonist. I began to realise he wasn’t exactly harmless in 1995, when he published “Thoughts of a baby lying in a child care centre”. “Call her a cruel, ignorant, selfish bitch if you like, but I will defend her,” thinks the baby. “She is my mother and I think the WORLD of her … The failure is mine … I hate myself…”

Unsurprisingly, it kicked up a storm. At the time I was the sole parent of three small children — who, I feel compelled to add, grew up into wonderful adults — and was lucky enough to access government-funded childcare. I was the only mother I knew who wasn’t crushed by guilt for having to work, but by then I had had my own argument with the oppressive and misogynist cult of motherhood.

Like many of his generation, perhaps the most privileged in the history of the Western world, Leunig’s career inscribes an arc from anti-capitalist, individualistic politics to anti-woke warrior. Although perhaps it’s more accurate to say that the world has moved on beyond him, and instead of responding to new voices in the polity, he has merely become more entrenched in what are now old and stale ideas.

In 2017, for instance, he drew a cartoon of a solitary Leunig-figure, with a banner saying “ME”, facing a menacing crowd with an “LGBTQ” banner. Appended are a couple of doggerel verses (doggerel verse is a major part of late-Leunig whimsy): “Lonely little weirdo / Minority of one / Nothing much to celebrate / Not a lot of fun / So much persecution / So much pain and strife / Lonely little everyone / Trying to make a life”.

This cartoon was published just after the bitter equal marriage campaign, which generated a horrific level of homophobic abuse. It illustrates both the egocentric switcheroo that characterises so much of Leunig’s less palatable work and the increasingly cloying whimsy that disguises its essential ugliness as “innocence”. Leunig expresses the anger of a man adrift in a world that questions his place at the apex of social power. He is unable to perceive that the structural forces that enable his privilege — and the suffering of others — are also the sources of his own discontent.

As Robbie Moore said in 2021 in MeanjinLeunig has embraced a “reactionary politics of male victimhood”:

Male privilege doesn’t exist, he argues in a 2017 essay: aren’t we all just humans? And there, in that argument, he betrays his privilege. As a white man, he’s never needed collective action to fight for his own status as human, to fight for basic rights and dignities.

People still love his work, and that’s their right. But it’s a love threaded with nostalgia for the free-wheeling, masculinist larrikinism of the 1970s. It was a time when men were real men, women were real women and troublesome minorities of every kind knew their place. If those times have passed, that is all to the good. No, we should not mourn that toxic nostalgia.

Read the opposing argument by Michael Smith.